A Night at Korakuen Hall, Tokyo

By: Shrey

Only a few short steps from Tokyo’s famously punctual Metro system, one can spot the towering Tokyo Dome[Sh1] — and right beside it, the iconic Korakuen Hall. While the Dome is better known for baseball, Korakuen has long stood as one of Tokyo’s most resilient symbols of boxing. As I wandered through the venue area, passing cozy food stalls and a small maze of winding staircases, I eventually navigated to the hall entrance. Up the 5th floor I was welcomed by thoroughly polite staff and directed to my seat for the March 31st Phoenix Battle “Lemino” boxing event.

Japan has a long and proud boxing tradition. From Fighting Harada — a two-division world champion in the 1960s — to the durable and technical Toshiaki Nishioka, and more recently, the slick, hard-hitting Takashi Uchiyama, Japanese boxing has produced fantastic representatives, especially in the lower divisions. Since 1970 Japan has usually had at least one reigning world champion at any given time. That said, few Japanese boxers had broken into global superstardom — until the emergence of Naoya “Monster” Inoue.

Inoue, known for his skill and knockout power, is arguably the most dominant fighter on the planet today, currently an undisputed world champion across two divisions (26–0 with 23 KOs). And on this particular night, I had the chance to watch Naoya’s cousin, Koki Inoue. A former Japanese and WBO Asia Pacific champion at 140 lbs., Koki was coming off a loss and looking to rebuild momentum in his career. That might explain why he was fighting on a Monday night — a near unseen timeslot by Western standards, for which boxing is typically paired with late night drinking and rowdy crowds. But the atmosphere at Korakuen Hall couldn’t have been more different.

The crowd, like the city it reflected, was eclectic and composed. Trendy girls who looked like they’d come straight from Shibuya sat next to older gentlemen who might’ve just clocked out of a late office shift[Sh2] . I noticed a handful of other foreigners as well, clearly already assimilated to the unspoken etiquette in the air. The arena was small, bringing us closer to the action and to each other as the night unfolded. Just like the Metro outside, the event ran like clockwork. The card featured six eight-round fights spanning divisions from Minimumweight to Super Welterweight. While the talent on display was clearly at the domestic level, each fighter looked to be in peak condition with tight, focused corners and clean, respectful boxing throughout.

The ring announcer brought strong energy, introducing each bout and round with enthusiasm. While all the announcements and signage were in Japanese, the dedication of the fighters needed no translation. The crowd stayed quiet during the rounds, but one got the sense it came from not boredom but respect,. Aalmost like they were studying nuanced art on display., Aas the boxers danced across the ring. No heckling, jeering or even much idle chatter – only attentive eyes fixed on the ring.

That atmosphere extended into the main event, where Koki Inoue (18-2) faced Russian fighter Mikael Lesnikov (8-6-1). Lesnikov is the definition of a road warrior, having fought in Vietnam, Korea, Australia, and more. Having likely experienced hostile welcomes as a foreign fighter before, he was appreciated how the crowd greeted him with polite applause; another sign of the respectful culture around us. Still, the crowd made their preference known with a much more enthusiastic welcome for Inoue’s entrance.

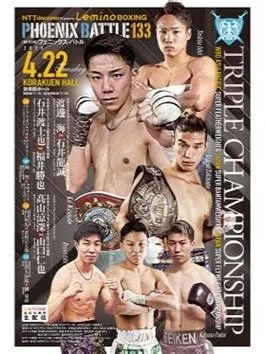

Phoenix Battle 133

The fight itself began as a classic southpaw vs. orthodox scramble. Lesnikov tried to push the pace early, looking for openings against the more reserved Inoue, but found few. The two circled and probed, trading single shots rather than flurries. It remained a tight, tactical affair until the end of Rround 2, when Inoue clipped Lesnikov with a looping right hook. Lesnikov complained to the ref that the shot landed behind his head, but Inoue pressed forward and landed another strike just before the bell. Lesnikov, seemingly out of frustration, hit Inoue with a lazy left in response after the bell had rung.

Lesnikov touched gloves to apologize, but what I noticed was the silent crowd reaction – as if they were disappointed by the breach in sportsmanship. I couldn’t help but contrast that with the boos or chaos such a move might’ve sparked back home.

Whether or not the move lit a fire under him, Inoue came out for Rround 3 looking sharper. He began stepping into his straight lefts more frequently, timing Lesnikov twice with strong shots to the head. He didn’t overcommit, though, showing patience with each success. Then, right near the end of the round, he dug a punishing left to the body. Lesnikov stepped in, beginning to clinch, but promptly dropped to his knees. For the first time, Korakuen erupted. The 10-count began, and Lesnikov could only manage crawling around the ring before the ref counted him out.

As Inoue gave a brief, humble post-fight speech and the crowd offered a final round of applause, I walked away with full appreciation for the event. Japanese boxing may not have the same media saturation as the U.S. or U.K., but there’s something powerful about watching respect permeate each aspect of how Japan embraces the sweet science. Though this wasn’t a championship-level bout, I look forward to viewing more Phoenix & Lemino[Sh3] cards in the future.

With Naoya Inoue continuing to elevate Japanese boxing on the global stage, and fighters like Koki still drawing crowds on weeknights, you can’t help but wonder how much higher the ceiling could be.